Street food vending is illegal in the Los Angeles County, but for some it is essential to their livelihoods.

While Central Avenue is no longer the center of Los Angeles’ jazz scene, it maintains an important connection to it today. LA’s most prominent jazz artists came through here.

In a neighborhood with only one mile of bike lanes, people are out to improve bicycle infrastructure and safety.

“Hola!” calls a lanky African-American girl to her teacher when she arrives at Main Street Elementary School on a Monday morning. She has cornrows, a pink backpack and contagious enthusiasm for what is already her second language.

Jaylyn is in first grade and her second year of bilingual classes. Her family speaks English, but most of her neighbors are native or exclusive Spanish speakers. She already knew some Spanish before kindergarten.

“They do fine because of the community they live in,” said Lisette Montes, who teaches kindergarten. “The majority of kids are already bilingual.”

Bilingual classes were introduced to Main Street Elementary last year, replacing traditional Structured English Immersion programs. Those programs focused on transitional skills, while bilingual education focuses on developing Spanish and English simultaneously.

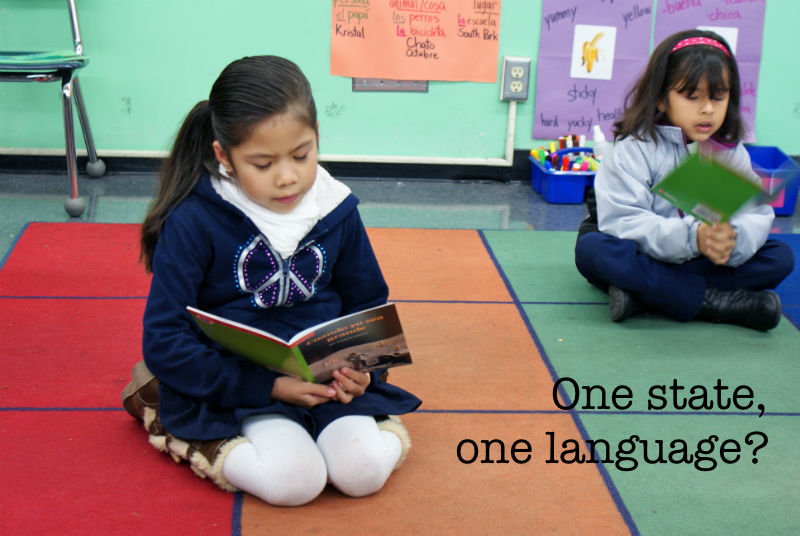

“A lot of parents don’t want their kids to learn Spanish,” said Mercedes Pineda, the school’s Bilingual Coordinator. “They say, no, we live in America, or no, I’ll teach them at home. And yes, you can teach them how to speak, but… there’s value in cognitively knowing and processing in those two languages.”

Pineda emigrated to South LA from El Salvador and learned English in an SEI program: Spanish-speaking students learned separately in Spanish, then later in English. To develop a second language (called L2 in linguistics) properly, a student must first understand and speak clearly in their native language, or L1.

“There’s a stigma to when you are the Spanish-dominant student in a bilingual program – you need this skill and you don’t have it,” said Eugenia Mora-Flores, an associate professor at the USC Rossier School of Education and native Spanish speaker. “[Parents] want their child to do well in this country and in their schools, and they don’t understand that bilingual programs use Spanish to further English teaching.”

Even in districts like LAUSD, where 41 percent of students are English learners, immersion programs are politically popular. They emphasize English acquisition, not Spanish development. For advocates with organizations like English First, teaching students in other languages destroys the purpose of a single national language. And for immigrant parents, English gives students access to economic and political power.

“People are still fighting an old battle. But the world has moved on,” said Fransisca Sanchez, another native Spanish speaker and president-elect of the California Association for Bilingual Education. “In many, many countries, students are routinely becoming high-level multilinguals in five or six languages.”

Plus, a vast majority of recent studies say multilingualism enhances cognition. While students’ test scores lag a little around third grade—the critical year for forming vocabulary and syntax skill—by fifth or sixth grade, even their math and science scores increase.

“Native English speakers outperform their native English-speaking peers who haven’t been in the [bilingual] program, even in areas like mathematics,”Sanchez said. These students are “elite bilinguals”—they may not need to learn a second language, but they choose to, instead of exclusively speaking English. “For people who are really serious about wanting to accelerate learning and achievement, well, dual-language programs have proven their success.”

The danger of outright immersion programs is “semi-lingualism,” Mora-Flores said. When a student begins learning an L2 without mastering L1, development of both languages is stunted, and the child’s vocabulary may be crippled for years.

For that reason, “Most people thought Main Street wasn’t the best place to do this,” said Pineda. South Central has one of the city’s highesttransiency rates—turnover peaked at 30 percent a few years ago—and for bilingual programs to succeed, students must attend consistently.

“Some kids could be enrolled this week, and a month later, they’ll be gone,” Pineda said.

But only one class in each grade level offers the bilingual curriculum, and attendance has been remarkably stable. Only one student from Montes’s class left the school this year. Four of her students’ families are moving but keeping their children at Main Street.

“When you have a quality school, people don’t want to leave,” Pineda said. “We’ve really worked to build a place that is safe and welcoming.”

Plus—and perhaps more importantly—language skills are inherently linked to cultural literacy. Pineda, a daughter of Salvadoran immigrants and mother of two, enrolled both her sons in bilingual programs.

“I want them appreciating the culture and the Spanish language,” she said.

“Language is such an integral part of who we are as human beings,” said Sanchez. When children lose their native language skills, “We have children who can no longer communicate with their parents or grandparents, no possibility of elders handing down their knowledge, their wisdom, their history, the information that allows a person to know who he or she is.”

In 2011, LAUSD and several hundred other California districts adopted the “Seal of Biliteracy,” debuted by pro-bilingual education group Californians Together. This award is a watermark on high school diplomas that recognizes students who are fully developed bilingual speakers.

“It’s a statement on behalf of the state in terms of that it values students who have those skills,” said Shelly Spiegel-Coleman, director of Californians Together. “It changes the conversation from looking at students who don’t speak English in a negative frame, to one where their potential is extremely positive.”

“There are so many benefits to biliteracy,” said Montes, the kindergarten teacher at Main Street Elementary. “In high school, they can go on to add a third language and become trilingual. There are many disadvantages in their neighborhood, and this is an advantage.”

Still, despite growing academic popularity, bilingual programs are expensive, and many districts are replacing them with quicker immersion programs. “It’s actually continued to grow in areas where there is a focus on the importance of bilingualism for English-dominant students,” Mora-Flores said. “But it’s continued to dissipate in districts that are Spanish dominant.”

If Main Street doesn’t maintain 20-person classes at each grade level, LAUSD may close the program, Pineda said. Both grades are hovering around that number now.

“That’s stressful,” Pineda said. “These kids are going to grow up someday, and you want to give them as many skills as possible.”

“Bilingual, that’s about speaking the language. Biliteracy, that’s being able to read it,” Montes said. That may be as much as students like Jaylyn can achieve. But for her Spanish-speaking classmates, "There is a combination between language and culture. And that's important.”