Chesterfield Square Park is home

to a cast of regulars and passers-through who together

create a dynamic, urban scene indicative of the time,

2012, and the place, South L.A.

SKIP INTRO ENTER SITE

EXIT

A haunting past, a new beginning

Regina Clifton refuses to let her scarring past define who she is today, although she will never forget the events that forced her to grow up young.

Power in Political Participation

South LA Power Coalition works to engage citizens of South LA politically. They are not affiliated with any party and hope to cross racial barriers to show citizens the power that comes from political participation.

They Call themselves the round table, but there's no question who's in charge

At Chesterfield Square Park, the so-called Round Table is rectangular, with 6,000 calories of Church's chicken plopped in the center.

But well-rounded is its motley cast of regulars that line the benches on either side, including both ex-cop and ex-convict, teenager and grandfather, victim and veteran.

But there's really only one Round Tabler you need to know if you're new at the park, and that's Courtney Mackey.

Mackey--known as Mimi, and known by everyone--is an important cog in the park's lively social scene, structured around its concrete picnic tables. You don't just walk up to any table in Chesterfield Square Park and take a seat; the park is segregated and few (Mackey being one of them) can get away with table-hopping.

"Anything you want to know about the park?" said Kirby Hayward, a big rig driver and Mackey's best friend. "You're talking to the encyclopedia right there. Mimi knows everything about everybody."

Mackey knows who sits at what table and can point something out about each person who passes through the park's main walkway: "we call him the human pooper scooper...there goes Lady Red Flag. You all think I'm ignorant? Lord have mercy...he's shroomed out, must be on that angel dust again."

"I just can't sit down like everybody else," Mackey said. "I got to get up and find out."

The park's set-up recalls a high-school lunchroom: there's a table for the poker-players, the pot-smokers, the "gangsters," some tables are all-Black, others all-Latino.

The Round Table, in the park's northwest corner, originated a few blocks from the park, in the Big Lots parking lot at Manhattan and Slauson, near the former site of an automotive shop owned by the brothers of a man named Connie Gordon. Gordon plays yin to Mackey's loud, tough yang: he’s the table's voice of reason, the devil's advocate during discussions, the mild temper and perpetual charm.

"Connie's got a white man's sense of humor," Mackey says.

He calls Mackey Rona Barrett, after the gossip columnist famous in the 70s and 80s. She calls him a number of names, all too crass to print.

The group that now meets twice weekly began as a way for Gordon and his brothers to keep up with some of the homeless men who'd hung around the garage before it closed in 1999. Men like Kenneth Pye, whom everyone calls Pye-dog, and Tommy Brooks, an artist, singer and sometimes-bike thief who claims to have more women than Howard Hughes has money.

"We'd come and give them food and beers and money, but after a period of time, it became a little hot because of the police," Gordon said of the cops' crackdown on the homeless guys' drinking and urinating near the lot. "So that's why we moved over here. [Police] come by the park but they don’t see anything but some old guys sitting here."

Now, they camouflage their alcohol consumption by pouring Budweiser in paper cups and sipping through plastic lids and straws, crushing up the cans and stashing them as they go.

Discussion topics range from sports to politics to crime, but Round Table banter isn't for the prudish: subjects like sex and drugs aren't skirted, name-calling is not euphemized, language is uncensored.

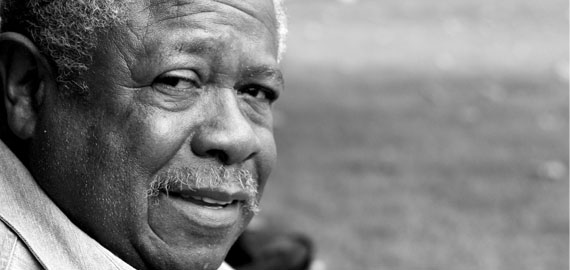

Gordon spent 30 years with LAPD, was one of the first Black cops on the force; now, he plays golf, referees basketball games at a gym in Carson, and spends time with his children and grandchildren.

Gordon's looked up to by many people at the park: he explains Mackey's court documents to her, listens to Paula Varnado describe the symptoms caused by her multiple sclerosis and reminds Cameron Duerson, the Round Table's youngest regular and a student at Los Angeles Trade Technical College, to finish his homework.

"When I grow up, I want to be like Connie," Duerson said.

But it's not all about giving for Gordon, there's something fulfilling for him about spending his afternoons at the park.

"I come from another part of life but I'm very comfortable here simply because the people here are very real," Gordon said. "Some of the folks that I worked with over the years were not nearly as real as the people here."

Continual budget cuts to the parks department forces the city to get creative

In 1914, the L.A. Park Commission announced rush plans to complete a four-acre park at the corner of 54th and Gramercy, saying it would resolve the city's "out-of-work problem" by hiring the unemployed for construction.

Called a "delightful little spot" by the L.A. Times, the blueprint for this park included a "charming little lily pond" at its center, "stately oriental palms" around its perimeter and "massive stone seats modeled upon the lines of ancient classic pieces from Pompeii."

Nearly a century later, the pond has dried up and the city seems to have lost interest in Chesterfield Square Park's well-being; maintenance is often left to the park's patrons. One such, Courtney Mackey, scrapes toilet seat covers off the wall in the bathroom after they're plastered up by a woman whose commentary with imaginary friends narrates her daily visits to the park.

"Right now it's very difficult," said Bernie Grerba, a Parks and Recreation department maintenance supervisor for two districts in South Los Angeles, one of which encompasses Chesterfield Square Park. "We're having to juggle; we're not really right on schedule all the time."

Park patrons say they've noticed a lag in the maintenance schedule--for a park like Chesterfield Square, this includes trash removal, bathroom cleaning and lawn mowing--but not much has changed.

"They do everything they used to do, but it's just not as frequent anymore," said Jeffrey Pope, who's been hanging out at the park for nearly seven years.

Pope and others at Chesterfield Park probably haven't felt the brunt of years of cuts to the parks department and countless staff layoffs, Grerba said.

Before switching to the maintenance side in the department a couple years ago, Grerba spent nearly 40 years as a city landscaper, working in the Griffith Park area.

"One large park would have a senior gardener and three gardener-caretakers and some part-timers," Grerba said. "And now we just have a roaming crew and a part-time person who is a resident to take care of the buildings."

Grerba says they've been soliciting the help of more and more to volunteers and outside groups to complete upkeep and development projects.

"The Parks Department has been reaching out to non-profits more; we work with them really closely," said Laura Hartzell, a project manager at the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust (LANTL).

LANTL creates and maintains urban parks and gardens from grants, donations and some public funding. Right now, they have almost a dozen new projects in various stages of planning and construction.

Near the Chesterfield Square area, they're responsible for 11th Avenue Family Park in Hyde Park and the Richardson Family Park near Adams and Vermont.

"The [city] parks could use a lot more maintenance and work," Hartzell said, "but I can't even believe how much they're able to do with [such] limited resources and so many parks."

While it's likely that the parks budget will continue to shrink, Grerba said, some city council members are supporting new funding models for parks, including new rules to allow more public-private funding options that passed in May.

Though park funding is often the first to go when the city budget needs to be trimmed, Hartzell says spaces like Chesterfield Square Park are vital to their surrounding communities, which is why LANTL works to create more like them.

"If you can have a place that kids can play and seniors can sit and talk, with trees, shade and plants," Hartzell said, "then that's important in itself."

LANTL was formed after a city park study in 2000 reported a severe shortage of green spaces in L.A.'s underserved neighborhoods.

Areas like the one surrounding Chesterfield Square Park are densely populated, with many apartment-dwellers, meaning lots of people lack the backyard situation of typical homes.

"A 20-by-20 backyard is a dream for some people," Grerba said. "So many in that area don't have it, so they have to rely on the park space."

A boy watched his park change as a new demographic moved in

Across Ruthelen Street from the park, one yard stands out; yellow stalks and ruffled green fronds spill out above a wrought-iron gate, obstructing the house behind it.

"The jungle," Jeffrey Almendares, 18, says, pointing to his yard. "We can see everything from over there, but you can't really see anything from here."

The hidden house looks out at the southeast corner of the park, where the Latinos tend to congregate in Chesterfield Square Park.

Almendares admits he doesn't leave his house much. He doesn't like crowds or most people and the next time he leaves--really gets out--he wants it to be for architecture school, but he watches what goes on at the park from the shaded privacy of his yard.

Since his family moved in seven years ago, Almendares has seen this corner of the park transform from empty and quiet to loud, littered and full of people.

"A couple years back it was just so much cleaner, you know," Almendares said. "Now that they're here, they gamble, litter, smoke...you know, drug use."

"They" are Almendares' dad and his friends, a group of men who almost all work as day laborers in construction, roofing, moving, gardening--whatever jobs they can pick up outside the Home Depot a couple blocks away off Slauson and Western, where contractors pick up temporary workers.

They, like the Black people who gather in the park's opposite corner, came to the park after being driven from other spots where they once met, playing cards on a piece of plywood balanced on a trash can down the street.

"When they decided to settle here," Almendares said, "the Black people were already in their groups away from us. [There's] not really discrimination, just different languages, differences in people."

Though the park is noticeably divided, both Almendares and several of the people who sit on the other side say this isn't because of racism.

Courtney Mackey, the park's primary table-hopper and know-it-all, says people are friendly with each other no matter where they sit. She's befriended some of the Latino men from the park's opposite corner.

But a few blocks up Gramercy Street, the men who sit outside the Antroj Belizean Dollar Store on 48th Street--a rag-tag convenience store with a 99-cent VHS rack out front--have a different attitude.

One man there who would identify himself only as David said he's an out-of-work contractor and blames the Latino day laborers for his unemployment after spending decades as a construction worker.

"The Latinos are sucking up all the work," he said, saying they aren't licensed and accusing them of gambling at the park with illegally attained cash.

Several workers and contractors refused to comment on such an accusation.

Though usually only with small bills and change, the gamblers' passing of cash during card games and dice-throwing is noticeable in a park occupied by many that are homeless and unemployed.

But not all the Latino men are there to gamble; Luis Ramos brings his kid to the park to play almost daily.

Ramos is originally from El Salvador, and says most of the people that gather in that corner of the park are from there or other Central American countries.

"It's cultural," Ramos says of their tendency to gather in a large group and eat Salvadoran delicacies like pupusas and atol de elote together. Some days, more than 20 men and a few women show up.

One elderly man, Rosalio Velasquez, collects donations in a shoebox with a picture of his late brother taped on it. His brother died Dec. 5, and Velasquez is trying to raise some money to give to his brother's family. Even though he knows most of the guys don't have much to spare, they've put money in the box.

Almendares says it's this spirit that works to cancel out the "cops [rolling through] every night, [the] helicopters, car chases, gunshots" that the neighborhood is more known for.

Though he says he never became that involved with the activity on the streets--the gangs and the crime--it's what he grew up with. Before living on Ruthelen, he lived in Pico Union, where there were less Blacks and more Latinos, but it was still "the ghetto."

"I've never left," Almendares said. "This is all I know."